On September 27, men, women and children streamed into Velusamypuram in Karur, Tamil Nadu, for a glimpse of their hero—the actor-turned-politician Vijay. By the time the chief of Tamilaga Vettri Kazhagam reached the venue, hours late, the crowd had swelled. If the organisers expected 10,000 people, more than 25,000 had gathered—tired, parched and squeezed in a heaving mass. When Vijay climbed onto a makeshift stage atop his bus, the crowd surged forward, triggering chaos. The crush turned deadly: 41 people, including 18 women and 10 children, were killed in the stampede and more than a hundred were left injured.

India has become a stampede country. Crowded events—political rallies, religious congregations and sporting revelries —carry with them the fear of a fatal crush. This year began with 30 people dying in a stampede at the Sangam area in Prayagraj during the Kumbh Mela, followed by 18 people getting killed in a crowd crush at the New Delhi Railway Station. In June, 11 people died in a stampede in Bengaluru as thousands turned up to celebrate the IPL win of Royal Challengers Bengaluru (RCB).

What is going wrong with crowd control in India? Technology can monitor a crowd, but it can’t read its mind. “Understanding crowd psychology is integral to effective crowd management,” says Kuladhar Saikia, former director general of police, Assam. “In a crowd, individuals lose their personal identity and responsibility, sharing instead the emotions, ideas and actions of a group.”

Modern tools like drones and AI-powered CCTVs can track gatherings in real time, but experts insist that technology alone cannot prevent disasters. Ultimately, it is human psychology that decides whether a gathering stays safe or turns tragic, as in Vijay’s rally.

The ability — or rather, the failure — of law-enforcement authorities to gauge the pulse of a gathering has shaped every major crowd disaster, in India and beyond. From the 1954 Kumbh Mela stampede in Allahabad (now Prayagraj) that killed 500, to the 2024 Hathras stampede that claimed 123 lives despite modern technologies, the missing link has always been an understanding of mass behaviour.

India, with its 1.5 billion people, is especially vulnerable. Yet global tragedies tell the same story—be it the catastrophic Al-Ma’aisim tunnel disaster in Mecca in 1990 with 1,426 dead, or the Halloween crowd crush in Seoul, South Korea, in 2022 that killed 159, they can all be traced back to misjudged estimates and inadequate preventive measures.

CRITICAL MASS

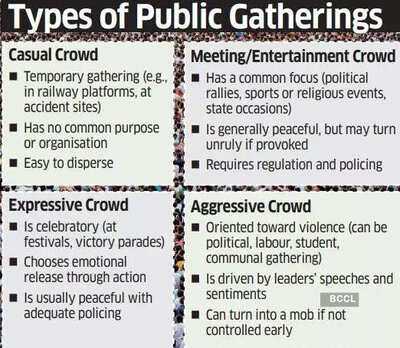

A 2025 document, “Comprehensive Guidelines on Crowd Control and Mass Gathering Management”, released by the Union Home Ministry’s Bureau of Police Research and Development (BPR&D), classifies public gatherings into four segments.

The first is the casual crowd—people with no common purpose, who gather at a railway platform or accident sites and are easy to disperse. The second is the meeting or entertainment crowd. They are seen at sports events, political rallies, religious congregations, or state ceremonies. They are usually peaceful, but can be unruly if provoked. The third is the expressive crowd—they dance, sing and celebrate during festivals or sports victories. They are emotional but typically manageable with adequate policing. The fourth is the aggressive crowd, oriented towards violence. The report says these are often political, labour, student or communal gatherings and are stirred by leaders and sentiments.

“The aggressive or unruly crowd gradually becomes a mob if it is not controlled in the early stages. The dividing line between a crowd and a mob is often indistinguishable. So long as the crowd is controlled by a show of force it is still considered to be in the crowd stage. But when force has to be used to control it, it is the mob stage,” the guidelines elaborate.

The document also invokes the theories of philosophers and psychologists who studied mass behaviour: French writer Gustave Le Bon, who put forward the idea of the collective mind; British psychologist William McDougall, who advanced the group mind theory; and Sigmund Freud, who spoke of primitive instincts lying dormant in the subconscious, surfacing in crowd situations.

“Crowd behaviour always differs from individual behaviour,” the report says. “This difference in crowd behaviour occurs because an individual’s inhibitions are eroded when he forms a part of a crowd. This happens due to the sense of anonymity that develops with the submerging of an individual’s identity in a crowd.”

Mumbai-based psychiatrist Shefali Batra says emotional stakes rise sharply in the presence of a charismatic figure like Vijay: “In such gatherings, even non-visual cues like sound or pushing can quickly escalate panic.”

Experts point out that the strength of a crowd is not necessarily the determining factor of a stampede. A 25,000-strong crowd at Vijay’s rally left 41 people dead, while more than 1.5 million mourners at singer Zubeen Garg’s funeral in Guwahati did not result in a single casualty. While Mumbai’s Marine Drive hosted the Indian cricket team’s 2024 victory parade in relative control, celebrations over RCB’s IPL win spiralled into chaos.

What matters is the police’s ability to read the scale and the nature of the assembly. “Law and order officials have to put their foot down,” says a senior police officer, who oversaw preparations for a Diljit Dosanjh concert in Chandigarh last year. The crowd was expected to touch 70,000, but organisers pushed for permission to serve alcohol. “I refused,” he says. “I may have looked like a bad cop, but that’s better than risking a stampede.”

ASSESS THE RISKS

Event managers say they have to balance emotionally charged audiences with strict standard operating procedures. The absence of clear regulations often exacerbates the situation. “There are no mandatory requirements for risk assessments in India,” says Rohan Oberoi, CEO of Momentum India, a Noida-based risk management firm. “That’s a huge gap, especially for political and religious gatherings.”

Preparation, though not a guarantee, is the best safeguard. The India tour of the rock band Coldplay earlier this year is a case in point. The planning began six months in advance. “The crowd at a concert stands near the stage, unlike cricket matches where people are seated,” says an organiser. A special software was developed to monitor the density of crowd with colour indicators, yet there were limitations. “Without thermal cameras, it was impossible to track headcounts after dark.”

“Each gathering is different,” says Bhanu Bhaskar, additional director general of police posted in Meerut, Uttar Pradesh. “Political rallies draw localised crowds with ideological divides. Religious events like the Kumbh Mela or Kanwar Yatra are spiritually driven yet highly emotional. Music concerts are more impulsive. The strategy has to change accordingly.” Crowd management today, he stresses, is no longer just about boots on the ground. “We’ve entered an era of AI-enabled CCTVs, real-time analytics and machine learning.”

For the Kanwar Yatra— which draws nearly 40 million devotees across five states — police deployed AI cameras to map routes and anticipate movement. “Whether there is a pipe burst, a fire, a drone scare, or even a rumour, our teams are trained to respond in seconds,” adds Bhaskar.

Sometimes, the right math can make all the difference. “Crowd management is also mathematics,” says Oberoi. “In a stadium, for instance, we calculate evacuation rates — 82 people per minute per metre of exit width on flat ground, and 66 if stairs are involved. From there, we reverse-engineer how many exits are needed, where barriers should go and how to funnel people safely.”

A stampede is no earthquake; there are warnings before it happens.

The next mega event on India’s calendar is the Simhastha Kumbh in Nashik in 2027. The Maharashtra town has to brace for an estimated 70-100 million visitors. Preparations PHOTO: PTI are underway, with many responsibilities handed to the Kumbhathon Innovation Foundation, a nonprofit tackling the logistical complexities of Kumbh and other mass gatherings by mobilising innovative solutions created by startups and students.

Safety upgrades are at the heart of this planning. Outdated structures like a 70-yearold Ram Setu bridge are being razed, while Rs 300 crore is being invested in 4,000 AI-enabled CCTV cameras and drone surveillance systems.

But are these measures enough to guarantee a zero-error congregation of such scale? Unlikely. Authorities must still account for the sudden flare of an aggressive or hostile crowd that chooses to defy protocols. History offers sobering reminders: in August 2003, at Nashik, police failed to divert a restive group of pilgrims into a planned route. This resulted in overcrowding on a walkway, leading to a tragic accident on a slope that claimed 29 lives.

In every large gathering, the ability to decode crowd psychology ultimately decides whether it becomes a celebration or a catastrophe.

India has become a stampede country. Crowded events—political rallies, religious congregations and sporting revelries —carry with them the fear of a fatal crush. This year began with 30 people dying in a stampede at the Sangam area in Prayagraj during the Kumbh Mela, followed by 18 people getting killed in a crowd crush at the New Delhi Railway Station. In June, 11 people died in a stampede in Bengaluru as thousands turned up to celebrate the IPL win of Royal Challengers Bengaluru (RCB).

What is going wrong with crowd control in India? Technology can monitor a crowd, but it can’t read its mind. “Understanding crowd psychology is integral to effective crowd management,” says Kuladhar Saikia, former director general of police, Assam. “In a crowd, individuals lose their personal identity and responsibility, sharing instead the emotions, ideas and actions of a group.”

Modern tools like drones and AI-powered CCTVs can track gatherings in real time, but experts insist that technology alone cannot prevent disasters. Ultimately, it is human psychology that decides whether a gathering stays safe or turns tragic, as in Vijay’s rally.

The ability — or rather, the failure — of law-enforcement authorities to gauge the pulse of a gathering has shaped every major crowd disaster, in India and beyond. From the 1954 Kumbh Mela stampede in Allahabad (now Prayagraj) that killed 500, to the 2024 Hathras stampede that claimed 123 lives despite modern technologies, the missing link has always been an understanding of mass behaviour.

India, with its 1.5 billion people, is especially vulnerable. Yet global tragedies tell the same story—be it the catastrophic Al-Ma’aisim tunnel disaster in Mecca in 1990 with 1,426 dead, or the Halloween crowd crush in Seoul, South Korea, in 2022 that killed 159, they can all be traced back to misjudged estimates and inadequate preventive measures.

CRITICAL MASS

A 2025 document, “Comprehensive Guidelines on Crowd Control and Mass Gathering Management”, released by the Union Home Ministry’s Bureau of Police Research and Development (BPR&D), classifies public gatherings into four segments.

The first is the casual crowd—people with no common purpose, who gather at a railway platform or accident sites and are easy to disperse. The second is the meeting or entertainment crowd. They are seen at sports events, political rallies, religious congregations, or state ceremonies. They are usually peaceful, but can be unruly if provoked. The third is the expressive crowd—they dance, sing and celebrate during festivals or sports victories. They are emotional but typically manageable with adequate policing. The fourth is the aggressive crowd, oriented towards violence. The report says these are often political, labour, student or communal gatherings and are stirred by leaders and sentiments.

“The aggressive or unruly crowd gradually becomes a mob if it is not controlled in the early stages. The dividing line between a crowd and a mob is often indistinguishable. So long as the crowd is controlled by a show of force it is still considered to be in the crowd stage. But when force has to be used to control it, it is the mob stage,” the guidelines elaborate.

The document also invokes the theories of philosophers and psychologists who studied mass behaviour: French writer Gustave Le Bon, who put forward the idea of the collective mind; British psychologist William McDougall, who advanced the group mind theory; and Sigmund Freud, who spoke of primitive instincts lying dormant in the subconscious, surfacing in crowd situations.

“Crowd behaviour always differs from individual behaviour,” the report says. “This difference in crowd behaviour occurs because an individual’s inhibitions are eroded when he forms a part of a crowd. This happens due to the sense of anonymity that develops with the submerging of an individual’s identity in a crowd.”

Mumbai-based psychiatrist Shefali Batra says emotional stakes rise sharply in the presence of a charismatic figure like Vijay: “In such gatherings, even non-visual cues like sound or pushing can quickly escalate panic.”

Experts point out that the strength of a crowd is not necessarily the determining factor of a stampede. A 25,000-strong crowd at Vijay’s rally left 41 people dead, while more than 1.5 million mourners at singer Zubeen Garg’s funeral in Guwahati did not result in a single casualty. While Mumbai’s Marine Drive hosted the Indian cricket team’s 2024 victory parade in relative control, celebrations over RCB’s IPL win spiralled into chaos.

What matters is the police’s ability to read the scale and the nature of the assembly. “Law and order officials have to put their foot down,” says a senior police officer, who oversaw preparations for a Diljit Dosanjh concert in Chandigarh last year. The crowd was expected to touch 70,000, but organisers pushed for permission to serve alcohol. “I refused,” he says. “I may have looked like a bad cop, but that’s better than risking a stampede.”

ASSESS THE RISKS

Event managers say they have to balance emotionally charged audiences with strict standard operating procedures. The absence of clear regulations often exacerbates the situation. “There are no mandatory requirements for risk assessments in India,” says Rohan Oberoi, CEO of Momentum India, a Noida-based risk management firm. “That’s a huge gap, especially for political and religious gatherings.”

Preparation, though not a guarantee, is the best safeguard. The India tour of the rock band Coldplay earlier this year is a case in point. The planning began six months in advance. “The crowd at a concert stands near the stage, unlike cricket matches where people are seated,” says an organiser. A special software was developed to monitor the density of crowd with colour indicators, yet there were limitations. “Without thermal cameras, it was impossible to track headcounts after dark.”

“Each gathering is different,” says Bhanu Bhaskar, additional director general of police posted in Meerut, Uttar Pradesh. “Political rallies draw localised crowds with ideological divides. Religious events like the Kumbh Mela or Kanwar Yatra are spiritually driven yet highly emotional. Music concerts are more impulsive. The strategy has to change accordingly.” Crowd management today, he stresses, is no longer just about boots on the ground. “We’ve entered an era of AI-enabled CCTVs, real-time analytics and machine learning.”

For the Kanwar Yatra— which draws nearly 40 million devotees across five states — police deployed AI cameras to map routes and anticipate movement. “Whether there is a pipe burst, a fire, a drone scare, or even a rumour, our teams are trained to respond in seconds,” adds Bhaskar.

Sometimes, the right math can make all the difference. “Crowd management is also mathematics,” says Oberoi. “In a stadium, for instance, we calculate evacuation rates — 82 people per minute per metre of exit width on flat ground, and 66 if stairs are involved. From there, we reverse-engineer how many exits are needed, where barriers should go and how to funnel people safely.”

A stampede is no earthquake; there are warnings before it happens.

The next mega event on India’s calendar is the Simhastha Kumbh in Nashik in 2027. The Maharashtra town has to brace for an estimated 70-100 million visitors. Preparations PHOTO: PTI are underway, with many responsibilities handed to the Kumbhathon Innovation Foundation, a nonprofit tackling the logistical complexities of Kumbh and other mass gatherings by mobilising innovative solutions created by startups and students.

Safety upgrades are at the heart of this planning. Outdated structures like a 70-yearold Ram Setu bridge are being razed, while Rs 300 crore is being invested in 4,000 AI-enabled CCTV cameras and drone surveillance systems.

But are these measures enough to guarantee a zero-error congregation of such scale? Unlikely. Authorities must still account for the sudden flare of an aggressive or hostile crowd that chooses to defy protocols. History offers sobering reminders: in August 2003, at Nashik, police failed to divert a restive group of pilgrims into a planned route. This resulted in overcrowding on a walkway, leading to a tragic accident on a slope that claimed 29 lives.

In every large gathering, the ability to decode crowd psychology ultimately decides whether it becomes a celebration or a catastrophe.

You may also like

'His bravery should not be forgotten': Suchir Balaji's father starts petition to rename AI Act after dead son

Ed Gein's real-life 'girlfriend' refused killer's marriage proposal for bizarre reason

Daryz wins £4.1m Prix de l'Arc de Triomphe in Aga Khan colours

SNDP leader alleges presence of 'secret groups' in Devaswom temples in Kerala

Did Ed Gein help capture Ted Bundy? Monster: The Ed Gein Story ending explained