Nicholas Kent, the Education Department official who oversees US universities, is largely staying out of the Trump administration’s showdown with Harvard and other elite schools. His approach to remaking higher education is less splashy but potentially more sweeping: Overhauling the accreditation system.

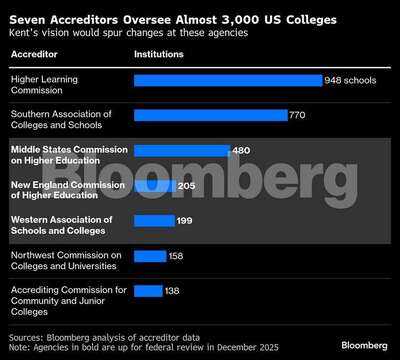

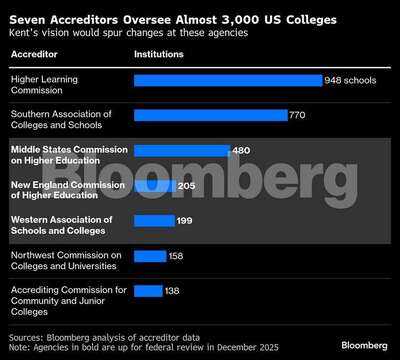

Colleges count on accreditors, the independent agencies that oversee their financial and academic standards, to approve their eligibility for federal funding. The Education Department has the power to rescind those agencies’ government recognition, a move that would effectively put them out of business.

President Donald Trump has called the accreditation system a “secret weapon” for forcing changes in academia. And Kent, having spent much of his career focused on this critical piece of higher ed infrastructure, is uniquely well-positioned to wield it.

The under secretary of education wants accreditors to enforce standards similar to commitments the White House has sought from elite schools, and pressure them to police campuses on issues like student protest crackdowns and DEI programs.

“We can no longer nibble around the edges. We need a reset of the whole system,” Kent said in an interview. “You could call it a revolution.”

By going after accreditation, the vein that connects all universities to their federal funding, Kent can make Trump’s policies course through the bloodstream of higher education.

In a hint at his priorities, Kent chose to give his first public address in the new role at a September meeting of accrediting agencies, where he declared, “Everyone should expect a dramatic overhaul of the accreditation system as it currently exists within the next year.”

Kent is implementing his plans to upend what he calls the “higher education industrial complex” from his Washington office just south of the National Mall, at the end of a city-block-length hallway lined with empty cubicles. In March, the Trump administration laid off about half of the department’s 4,100-person staff, and in October they moved to fire roughly 500 more. Kent and his boss, Education Secretary Linda McMahon, are intent on dismantling the department and putting themselves out of their jobs.

Kent is implementing his plans to upend what he calls the “higher education industrial complex” from his Washington office just south of the National Mall, at the end of a city-block-length hallway lined with empty cubicles. In March, the Trump administration laid off about half of the department’s 4,100-person staff, and in October they moved to fire roughly 500 more. Kent and his boss, Education Secretary Linda McMahon, are intent on dismantling the department and putting themselves out of their jobs.

But first they’re aiming to expand a campus pressure campaign that has frozen billions in federal research dollars and targeted international students. More recently, the White House invited schools to join a compact promising preferential funding in exchange for a commitment to key policy priorities.

The compact is voluntary, though, and so far, institutions from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to the University of Pennsylvania have rejected it. If the Education Department can strong-arm accreditors into adopting similar terms as standards, it could have a powerful effect.

That reality is not lost on Kent, a policy wonk who has deep familiarity with the accreditation system. He began his career working for an accreditor of vocational health education programs in the 2000s before moving to a trade-school lobbying organization that pushed for quicker paths to accreditation. In 2023 he was appointed deputy education secretary of Virginia, where he continued to pursue accreditation reform.

“He understands we can’t keep doing things the way we’ve always done in higher ed,” said Virginia Secretary of Education Aimee Guidera, Kent’s former boss. “His experience in the accreditation world was tremendously helpful on that front.”

Christopher Rufo, the conservative activist who's been quietly influential in shaping Trump's education policy, told Bloomberg in July that the administration “should turn the screws on accreditors and use them as a proxy for reform.”

The Trump administration has already begun to test the waters. In April the White House released an executive order to “reform” the accreditation system, calling agencies “gatekeepers” who had “abused their enormous authority.”

In June, as the White House battled with Columbia University over alleged campus antisemitism with $400 million in federal funds at stake, the department declared that the school had run afoul of its accreditation, a finding that could lead to having its recognition pulled. Columbia’s accreditor, the Middle States Commission on Higher Education, warned the school that it was at risk of violating its standards but never went so far as to revoke its certification.

The White House repeated the tactic in July with Harvard. The school’s accreditor, the New England Commission of Higher Education, has yet to take action.

“It is the expectation of the department that the accreditors look into these issues,” Kent said. “We're not afraid to fire accreditors if it comes down to it.”

It’s not an empty threat. Over the summer, the department pushed back the annual meeting of its National Advisory Committee on Institutional Quality and Integrity, which is responsible for recertifying accreditors, from July to this month; it was delayed again due to the government shutdown and is now scheduled for December. By then, six of the 18 board members are set to be replaced by McMahon appointees. The delays have raised concerns about plans for the accreditors of Columbia and Harvard, which are scheduled to face a compliance review.

Decertifying major accreditors like MSCHE and NECHE, which together oversee nearly 700 US schools, could sow chaos: Their members would scramble to switch agencies to avoid losing federal funding, and unrecognized accreditors would likely see their finances collapse as the member dues that fund their operations dry up.

For the Trump administration, that kind of disruption is “a shot they can fire across the bow,” said Barbara Brittingham, a former NECHE president.

Revoking accreditors’ recognition is not without precedent. In 2022 the Biden administration terminated recognition for an agency that oversaw for-profit and trade schools, saying it did not uphold adequate educational standards. Kent said that failing to enforce the administration’s view of civil rights law is an equally good justification for pulling an accreditor’s recognition.

Using the regulatory infrastructure in that way would be “a political power grab, not a quality improvement plan,” said Antoinette Flores, director of higher education accountability and quality at the think tank New America and a former Biden administration official overseeing accreditation issues.

Some agencies are already adapting. The Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges was a target of Governor Ron DeSantis’ efforts to upend higher education in Florida. The agency’s president, Stephen Pruitt, has been quick to reorient it since he stepped into the role in August. Last month he oversaw a “comprehensive audit” of SACS’ standards, including a “bias review” and a plan to focus more on workforce programs.

“We have baggage,” Pruitt conceded. “My job is to come in and rebuild trust.”

Meanwhile, MSCHE is relaxing its enforcement of DEI guidelines and on October 7 announced a comprehensive review of its standards. NECHE has proposed removing DEI standards, and the Western Association of Schools and Colleges Senior College and University Commission eliminated theirs earlier this month.

Pruitt said accreditors would “have to have their heads in the sand” to ignore pressures from the Education Department. At the same time, he added, it’s getting harder to see the line between regulatory compliance and political submission.

“Our job is to measure quality, not be ideological,” he said. “The eye of the needle that we have to thread there keeps getting smaller and smaller.”

Kent also wants to open the sector to more agencies and disrupt the “little monopolies” that he says the major accreditors hold.

That could funnel federal dollars to certificate programs, trade schools and for-profit colleges that have struggled to survive the drawn-out accreditation process.

Stratsi Kulinski founded NewU University, an experimental three-year college in Washington, and he’s been stuck in what he calls “the accreditation black box” since applying for that certification in 2022. Easing the bureaucracy around recognition could help entrepreneurs like Kulinski get their programs off the ground.

New accreditors could serve not just upstarts like NewU, but also small colleges struggling to stay in good financial standing with legacy agencies. They could also dilute the influence of the major accreditors.

Aspiring accreditors are already positioning themselves as Trump-friendly alternatives. Six public university systems in red states are launching a new accreditor, an effort helmed in part by DeSantis that he described as an endeavor to “upend the monopoly of the woke accreditation cartels.” Others are incorporating terms like viewpoint diversity into their proposed standards.

Aspiring accreditors are already positioning themselves as Trump-friendly alternatives. Six public university systems in red states are launching a new accreditor, an effort helmed in part by DeSantis that he described as an endeavor to “upend the monopoly of the woke accreditation cartels.” Others are incorporating terms like viewpoint diversity into their proposed standards.

“All of the new agencies seeking recognition are trying to espouse the administration’s values,” Flores said.

Kent is encouraged by new entrants and hopes to see more. He said his bifurcated approach of cracking down on established agencies while easing restrictions for new ones serves the same goal: Transforming higher education.

If the traditional academic pecking order is disrupted in the process, so be it.

“As we think about a new accountability structure, there will be winners and losers,” he said.

Colleges count on accreditors, the independent agencies that oversee their financial and academic standards, to approve their eligibility for federal funding. The Education Department has the power to rescind those agencies’ government recognition, a move that would effectively put them out of business.

President Donald Trump has called the accreditation system a “secret weapon” for forcing changes in academia. And Kent, having spent much of his career focused on this critical piece of higher ed infrastructure, is uniquely well-positioned to wield it.

The under secretary of education wants accreditors to enforce standards similar to commitments the White House has sought from elite schools, and pressure them to police campuses on issues like student protest crackdowns and DEI programs.

“We can no longer nibble around the edges. We need a reset of the whole system,” Kent said in an interview. “You could call it a revolution.”

By going after accreditation, the vein that connects all universities to their federal funding, Kent can make Trump’s policies course through the bloodstream of higher education.

In a hint at his priorities, Kent chose to give his first public address in the new role at a September meeting of accrediting agencies, where he declared, “Everyone should expect a dramatic overhaul of the accreditation system as it currently exists within the next year.”

But first they’re aiming to expand a campus pressure campaign that has frozen billions in federal research dollars and targeted international students. More recently, the White House invited schools to join a compact promising preferential funding in exchange for a commitment to key policy priorities.

The compact is voluntary, though, and so far, institutions from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to the University of Pennsylvania have rejected it. If the Education Department can strong-arm accreditors into adopting similar terms as standards, it could have a powerful effect.

That reality is not lost on Kent, a policy wonk who has deep familiarity with the accreditation system. He began his career working for an accreditor of vocational health education programs in the 2000s before moving to a trade-school lobbying organization that pushed for quicker paths to accreditation. In 2023 he was appointed deputy education secretary of Virginia, where he continued to pursue accreditation reform.

“He understands we can’t keep doing things the way we’ve always done in higher ed,” said Virginia Secretary of Education Aimee Guidera, Kent’s former boss. “His experience in the accreditation world was tremendously helpful on that front.”

Christopher Rufo, the conservative activist who's been quietly influential in shaping Trump's education policy, told Bloomberg in July that the administration “should turn the screws on accreditors and use them as a proxy for reform.”

The Trump administration has already begun to test the waters. In April the White House released an executive order to “reform” the accreditation system, calling agencies “gatekeepers” who had “abused their enormous authority.”

In June, as the White House battled with Columbia University over alleged campus antisemitism with $400 million in federal funds at stake, the department declared that the school had run afoul of its accreditation, a finding that could lead to having its recognition pulled. Columbia’s accreditor, the Middle States Commission on Higher Education, warned the school that it was at risk of violating its standards but never went so far as to revoke its certification.

The White House repeated the tactic in July with Harvard. The school’s accreditor, the New England Commission of Higher Education, has yet to take action.

“It is the expectation of the department that the accreditors look into these issues,” Kent said. “We're not afraid to fire accreditors if it comes down to it.”

It’s not an empty threat. Over the summer, the department pushed back the annual meeting of its National Advisory Committee on Institutional Quality and Integrity, which is responsible for recertifying accreditors, from July to this month; it was delayed again due to the government shutdown and is now scheduled for December. By then, six of the 18 board members are set to be replaced by McMahon appointees. The delays have raised concerns about plans for the accreditors of Columbia and Harvard, which are scheduled to face a compliance review.

Decertifying major accreditors like MSCHE and NECHE, which together oversee nearly 700 US schools, could sow chaos: Their members would scramble to switch agencies to avoid losing federal funding, and unrecognized accreditors would likely see their finances collapse as the member dues that fund their operations dry up.

For the Trump administration, that kind of disruption is “a shot they can fire across the bow,” said Barbara Brittingham, a former NECHE president.

Revoking accreditors’ recognition is not without precedent. In 2022 the Biden administration terminated recognition for an agency that oversaw for-profit and trade schools, saying it did not uphold adequate educational standards. Kent said that failing to enforce the administration’s view of civil rights law is an equally good justification for pulling an accreditor’s recognition.

Using the regulatory infrastructure in that way would be “a political power grab, not a quality improvement plan,” said Antoinette Flores, director of higher education accountability and quality at the think tank New America and a former Biden administration official overseeing accreditation issues.

Some agencies are already adapting. The Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges was a target of Governor Ron DeSantis’ efforts to upend higher education in Florida. The agency’s president, Stephen Pruitt, has been quick to reorient it since he stepped into the role in August. Last month he oversaw a “comprehensive audit” of SACS’ standards, including a “bias review” and a plan to focus more on workforce programs.

“We have baggage,” Pruitt conceded. “My job is to come in and rebuild trust.”

Meanwhile, MSCHE is relaxing its enforcement of DEI guidelines and on October 7 announced a comprehensive review of its standards. NECHE has proposed removing DEI standards, and the Western Association of Schools and Colleges Senior College and University Commission eliminated theirs earlier this month.

Pruitt said accreditors would “have to have their heads in the sand” to ignore pressures from the Education Department. At the same time, he added, it’s getting harder to see the line between regulatory compliance and political submission.

“Our job is to measure quality, not be ideological,” he said. “The eye of the needle that we have to thread there keeps getting smaller and smaller.”

Kent also wants to open the sector to more agencies and disrupt the “little monopolies” that he says the major accreditors hold.

That could funnel federal dollars to certificate programs, trade schools and for-profit colleges that have struggled to survive the drawn-out accreditation process.

Stratsi Kulinski founded NewU University, an experimental three-year college in Washington, and he’s been stuck in what he calls “the accreditation black box” since applying for that certification in 2022. Easing the bureaucracy around recognition could help entrepreneurs like Kulinski get their programs off the ground.

New accreditors could serve not just upstarts like NewU, but also small colleges struggling to stay in good financial standing with legacy agencies. They could also dilute the influence of the major accreditors.

Aspiring accreditors are already positioning themselves as Trump-friendly alternatives. Six public university systems in red states are launching a new accreditor, an effort helmed in part by DeSantis that he described as an endeavor to “upend the monopoly of the woke accreditation cartels.” Others are incorporating terms like viewpoint diversity into their proposed standards.

Aspiring accreditors are already positioning themselves as Trump-friendly alternatives. Six public university systems in red states are launching a new accreditor, an effort helmed in part by DeSantis that he described as an endeavor to “upend the monopoly of the woke accreditation cartels.” Others are incorporating terms like viewpoint diversity into their proposed standards. “All of the new agencies seeking recognition are trying to espouse the administration’s values,” Flores said.

Kent is encouraged by new entrants and hopes to see more. He said his bifurcated approach of cracking down on established agencies while easing restrictions for new ones serves the same goal: Transforming higher education.

If the traditional academic pecking order is disrupted in the process, so be it.

“As we think about a new accountability structure, there will be winners and losers,” he said.

You may also like

Eurozone inflation slows to 2.1% in October

I yearn for James Bond-style weaponry to take out selfish b******s littering

'I led Man City to the title but told friends I could be the next Man Utd manager'

Winter fuel payment lands in accounts from Saturday but 5 groups won't be eligible

Why is LeBron James not playing tonight vs the Memphis Grizzlies? Latest update on the Los Angeles Lakers star's injury report (October 31, 2025)